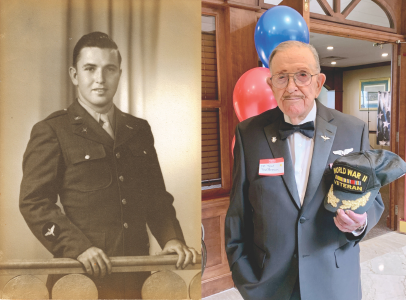

Last year, Dr. Tom Fitzpatrick finally decided it was time to stop working. He was 99, and he had kept the accelerator down his entire life; first as a decorated U.S. airman, then an accomplished scientist, and finally a closing chapter as president of a horseman's club he helped found and run from his 60s into his late 90s. He has lived his life to the fullest so far, and he’s earned the privilege of some serious rest and relaxation.

Last year, Dr. Tom Fitzpatrick finally decided it was time to stop working. He was 99, and he had kept the accelerator down his entire life; first as a decorated U.S. airman, then an accomplished scientist, and finally a closing chapter as president of a horseman's club he helped found and run from his 60s into his late 90s. He has lived his life to the fullest so far, and he’s earned the privilege of some serious rest and relaxation.

Upon stepping down as the president of the Philadelphia Saddle Club, he closed the book on a rewarding second chapter of his life where he set up a shared ownership member club for horseman and women. For a minimal initiation fee and just a few hundred dollars each month, members can ride as many times a week as they wish.

“My grandfather was a horseman,” recounted Fitzpatrick. “He always had a love of horses, so I suppose it was in my blood, but I didn’t start riding until very late in life. The saddle club started with 20 horses but has been streamlined down to 5 horses and 15 people.”

Rewind to 1943, five years into the global turmoil of WW2, Fitzpatrick was 22 years old and had joined the 2nd Bomb Group/96th Bombardment Squadron for the United States Army Air Corps. He had left a promising job with the USDA in order to serve his country. He became a radio operator/navigator assigned to a B-17 bomber, a type of plane most often used for daytime raids over Germany. One of Hitler’s competitive advantages was control over a series of industrial areas and oil refineries in Ploiesti, Romania. From high above in his four engine aircraft, Fitzpatrick went to work trying to disrupt the Nazi’s main supply of oil.

“Our goal was to win the air game against the Nazis,” remembered Fitzpatrick. “Towards the end of the war they didn’t have enough gasoline to put their planes in the air, which was in part due to our efforts.”

Fitzpatrick flew 25 missions for which he earned several military distinctions. Shortly after the end of the war he thought he might be needed in the far east, but he was able to return to his position with USDA. Under the provisions of the GI bill, they had to hold a job for him.

After the service, Fitzpatrick continued his education and earned his Bachelors of Science from Penn State, his Masters in Microbiology from AGNR and his Ph.D. from UMass Amherst. He remembers having to work very hard and enjoyed the university’s proximity to Washington D.C., where he made it a priority to visit every attraction he could.

With AGNR training as his foundation, he went on to become a career biochemist. He helped develop prenatal vitamins and is credited with discovering the base formula of vitamin b-12 and folic acid. He also contributed to the discovery of Lactaid for the lactose intolerant.

Fitzpatrick never married but instead channeled his energy into caring for his parents.

“I’m happy with my decisions to work hard, and maintain devotion to my parents. We traveled extensively and enjoyed each other's company.

Fitzpatrick certainly lived a full and charmed life with memories that he remembers fondly and without any hint of regret. Maybe it was the audience he held with and the blessing he received from Pope Pius XII in 1944 that put him on such a righteous path of belief and self-determination. Regardless, Fitzpatrick has reached a century in age, and judging by his remarkable recall and zest for life, he may just make it to his ultimate goal. “I always expected to get to 100 years! As chapter 6 verse 3 from the Bible states ‘May you live to be 120 years’. That’s my plan.”

by Graham Binder : Momentum Magazine Winter 2025