Featured Story

By Dr. Aditi Dubey

Research Associate, Hughes Center

Maryland’s legislature significantly updated the 1991 Forest Conservation Act through HB 723/SB 526 in 2023. The legislation was largely informed by a study published in 2022 by the Hughes Center, the Chesapeake Conservancy, and the University of Vermont Spatial Analysis Lab. This article focuses on one specific subject addressed in the bill that was included in our study: forest mitigation banking.

According to the FCA, development projects in the state must fulfill certain reforestation or afforestation requirements to minimize forest loss. One option for fulfilling those requirements is purchasing credits in a privately owned forest mitigation bank, where forests are protected in perpetuity.

Maryland has two types of mitigation banks: those that protect existing forests (retention banks) and those where new trees are planted (planted banks). In 2020, the Maryland attorney general released an opinion that retention banks do not comply with the FCA, which defines forest mitigation banks as: “the intentional restoration or creation of forests undertaken expressly for the purpose of providing credits for afforestation or reforestation requirements with enhanced environmental benefits from future activities.”

Subsequently, the Tree Solutions Now Act of 2021 disallowed the creation of new retention banks after December 31, 2020, and only permitted existing ones to sell credits until June 30, 2024. The act also commissioned the Hughes Center to research forest mitigation banking in the state as part of the previously mentioned report.

We found that as of spring 2022, 18 Maryland counties had provisions for banking programs within their regulations, 15 of which had at least one bank. Across the state, retention banks were far more widespread than planted ones, comprising 13,997 acres or 81.1% of reported bank acreage, while planted banks only made up 3,261 acres or 18.9%. In talking to county employees who run banking programs to understand the disparity between bank types better, they identified several reasons against getting rid of retention banks.

The basic environmental argument against retention banks is that replacing cleared trees by protecting existing ones still results in a net loss of trees. However, without the option of creating retention banks, landowners may turn to clearing or development to profit from their forested land, resulting in overall forest loss. Off-site preservation through retention banks must be provided at a 2:1 ratio, so the amount of existing woodland that is protected is twice the requirement for planted trees, allowing the protection of more acres in existing forests. Well-intentioned tree planting efforts can fail because of the significant time, investment and maintenance required to develop newly planted trees into healthy, mature forests that provide the full suite of desired ecosystem services. According to one county employee, to fulfill the FCA goals, we should use every tool at our disposal, including preserving existing trees to maintain a stable baseline forest canopy.

Compared to retention banks, planted banks require a much larger investment of time and money from landowners. According to the Forests for the Bay program, establishing 10 acres of trees costs 10 times more than protecting 10 acres. Therefore, simply replacing retention banks with planted ones may pose a steep challenge.

Finally, when no on- or off-site mitigation options are feasible, developers must pay the county’s Forest Conservation Fund, which must be used for afforestation or reforestation within a set time. Counties reported that without new retention banks, they struggled to contend with much higher numbers of these payments than before.

These were some of the concerns presented to the legislature by stakeholders, in addition to the negative impacts of disallowing retention banks on development and housing in the state. With all this in mind, the new legislation provides updated guidelines for mitigation banks.

New retention banks are allowed once more; however, they can only be used to fulfill up to 50% of a project’s afforestation or reforestation requirements, or up to 60% in special cases. To maximize the ecosystem services forests provide, retention banks can only be established in priority retention areas such as 100-year floodplains, stream buffers and forests suitable for interior forest-dwelling species.

To reduce impacts on development, the legislation also provides new alternative mitigation options, such as restoring on- or off-site degraded forests through steps like removing invasive species and controlling wildlife. Finally, the deadline for using money deposited in Forest Conservation Funds has been increased from 2 to 5 years, giving counties more time and flexibility.

These new policies will help Maryland reach its forest conservation goals while balancing environmental and practical considerations. To learn about the other important changes made through HB 723/SB 526, see the full text at: https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/mgawebsite/Legislation/Details/HB0723?ys=2023RS.

Study Finds Forests Conservation Measures Successful in Reducing Maryland Forest Loss, State Has Opportunity to Achieve Net Forest Gain

30 Years After Forest Conservation Act, New Monitoring Data Assess the Health of One of Maryland’s Most Important Natural Resources

A study released November 16 by the Harry R. Hughes Center for Agro-Ecology and conducted together with the Chesapeake Conservancy and the University of Vermont is the most comprehensive study of Maryland’s forest cover and tree canopy ever completed.

The study finds that over time, Maryland’s rate of forest loss has declined and the state is approaching a goal of achieving no net forest loss. With State priorities focused on tree plantings and increased funding available for land protection and agricultural conservation practices, the state has the opportunity to soon achieve no net forest loss and tip the balance towards forest gain.

At regional and county scales, patterns of forest change vary widely, and some concerning trends continue. Counties in central Maryland with rapid development and population growth experienced greater rates of loss, especially loss associated with development. While forest levels as a whole are stabilizing, continued urbanization is fragmenting forests and encouraging spread of invasive species. Fragmentation and invasive species spread are likely to continue given current patterns of change, especially in rapidly growing areas of the state.

The Technical Study on Changes in Forest Cover and Tree Canopy in Maryland, or Maryland Forest Technical Study, uses high-resolution data to analyze forest and tree canopy change at the local scale and provide a greater understanding of the key drivers of change. Insights derived from the study may be helpful to develop recommendations and policies that shift the balance to meet Maryland’s forest cover and tree canopy goals. The partners made several recommendations as a result of this study, including improving monitoring through technological innovation, addressing the loss of tree canopy outside forests and assessing causes of tree canopy change within forest blocks.

The study was conducted by the Hughes Center, Chesapeake Conservancy and the University of Vermont Spatial Analysis Lab in consultation with the Chesapeake Bay Program, and an Advisory Committee comprised of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, the Department of the Environment, the Department of Planning, the Department of Agriculture and the Chesapeake Bay Program. In an effort to improve Maryland’s statewide inventory of forest and tree canopy cover and assess forest and tree canopy change and the effectiveness of Maryland’s forest and tree programs, the Maryland Senate enacted a bill authorizing the study in 2019.

This report was supported by a grant from the Harry R. Hughes Center for Agro-Ecology utilizing funding from the State of Maryland, awarded following an open Request for Proposal (RFP) process.

As the Forest Conservation Act reached 30 years in practice in 2021, this is an important occasion to mark the successes of Maryland’s forest protection legislation and reflect on opportunities to further leverage forests and tree canopy to enhance benefits for habitat, water quality protection, climate resilience and mitigation, human health and environmental justice.

Read The Full Forest Study Here

Additionally, an associated online StoryMap provides the opportunity to view and interact with data and results produced in support of this study: cicgis.org/portal/apps/storymaps/stories/b519e88ccc8c4c4c8d4c870f64e210ed.

Quotes

“The findings from this study are key for decision-makers at both the statewide and local levels as they consider future strategies for trees and forests," said Harry R. Hughes Center for Agro-Ecology Executive Director Dr. Kate Everts. "This study comes at a critical time in Maryland as populations continue to increase and as we consider the future of Chesapeake Bay restoration. The Hughes Center is grateful for the opportunity to release this study and help tell the story of changes among our forests and trees so that science-based decisions can drive Maryland’s approach to protect them into the future.”

“It is notable that since 2000, forest loss slowed across Maryland while population grew nearly 17% and areas of loss are concentrated in a few rapidly growing counties,” said Chesapeake Conservancy’s Vice President for Climate Strategy Susan Minnemeyer. “This study provides key insights into tangible progress in increasing tree cover and tools local governments can use for planning future forest investments. Forests are green infrastructure for strengthening our communities, providing clean water and greater climate resilience. ”

“Information is power,” said Chesapeake Conservancy’s Executive Vice President Mark Conway. “As our state works to restore the health of the Chesapeake Bay and deals with the effects of climate change, utilizing the latest high-resolution land cover data to study forest and tree canopy is one of the most valuable tools in our toolbox. Trees are our best protectors from storm surges, floods, sea-level rise and extreme temperatures. They play a major role in water filtration, stormwater mitigation, air pollution removal, climate resilience and carbon sequestration. Trees are one of Maryland’s most important natural resources. In fact, our health, our environment and our economy all depend on trees.”

“It is crucial that our elected officials have the best information possible to make informed decisions about our natural resources that impact the health of our residents and the viability of the landscapes that sustain us,” said University of Vermont Director of the Spatial Analysis Laboratory Jarlath O’Neil-Dunne. “We are proud to have assisted in this important project that sets the standard for statewide forest assessment.”

Key Findings

Maryland’s Existing Forest Cover and Tree Canopy

Maryland’s forests cover 2.448 to 2.566 million acres of the state’s land area, according to the USDA Forest Service Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) program and the Chesapeake Bay Program Office (CBPO). When tree canopy outside forests is included, the state’s total tree canopy covers an estimated 3.095 million acres (CBPO). Percent forest cover estimates range from 39-42% of the state’s total land area, depending on the dataset and approach used (FIA, CBPO). Findings from three independent data sources (FIA, CBPO, and the National Land Cover Dataset or NLCD) agree on similar trends in Maryland’s forests. Forest area has shown a slightly decreasing trend over 5- and 20-year intervals but with a trend toward stabilization in the past 10 years (-0.14% annually from 2013-2018; -0.23% annually from 1999-2019). The decrease in forest cover has been offset somewhat by an increase in tree canopy outside forests, resulting in a more modest decrease in the total tree canopy (-0.077% annually). Despite the slightly decreasing, yet now stabilizing, trend, the state’s tree canopy has been remarkably stable given considerable increases in human population over the same period (876,000 people or nearly 17% growth from 2000-2020).

(Note: See Table ES-1 on Page 9 of the study)

Potential Locations for Afforestation and Reforestation

This study identified 373,506 acres of potential afforestation and reforestation locations in Maryland. Prioritization of planting sites will rely on further evaluation of available locations providing the greatest benefits from increasing tree canopy, financial resources and landowner interest. If Maryland wants to increase its forest cover, afforestation and reforestation, along with protection for existing forest, will be essential.

Health and Quality of Maryland’s Forests

This study examined both fragmentation and disturbance (including from invasive species) in Maryland’s forests. Forest structure throughout the state can generally be described as a patchy mosaic interspersed with other land cover types and infrastructure. The analysis shows the forest landscape became increasingly fragmented from 2013 to 2018, with the majority of trees in forested areas classified as edge or small patches. These types of fragmentation often have less habitat value and higher vulnerability compared to interior or core forest and increase pressure on species that require large, continuous intact forest tracts. Ground observations at USDA Forest Service’s Forest Inventory and Analysis plots between 2013-2019 indicated that approximately 12% of forests in Maryland experienced recent disturbance, with invasive species being the largest risk factor. The most frequent invasive plant species were multiflora rose, Japanese honeysuckle, Nepalese Browntop, and garlic mustard. Over the last 20 years, many of Maryland’s ash and hemlock trees have suffered damage or death from the Emerald Ash Borer and Hemlock Woolly Adelgid infestations.

Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement of 2014: Progress towards Expanding Urban Tree Canopy Acres and Riparian Forest Buffers

The Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement of 2014 (2014 CBA) committed Chesapeake Bay jurisdictions to collectively plant a total of 2,400 acres of trees in urban areas (here meaning census urbanized areas and urban clusters) by 2025. This analysis identified 4,665 acres of new tree canopy cover in urban areas between 2013 and 2018, but a loss of 17,829 acres, for a net decrease of 13,164 acres). From 2018-2020 (following this study interval), at least 30,000 trees have been planted in urban areas, cumulatively amounting to 85 additional acres. However, this study still indicates a significant net loss of urban tree acreage over the years 2013-2020.

Maryland has also committed to planting trees in streamside areas until 70% of riparian areas in the Chesapeake Bay watershed are forested. Our desktop analysis found 33% of Maryland’s jurisdictions (8) have reached the 2014 CBA goal of 70% of riparian areas under forest, while four jurisdictions (Baltimore City, Dorchester, Somerset, and Wicomico) still have less than 50% tree canopy cover in riparian areas. Trees planted more recently were not detected, as it can take up to 10 years for new trees to appear in remotely sensed high-resolution imagery, though they still provide a significant addition to emerging canopy cover in the state.

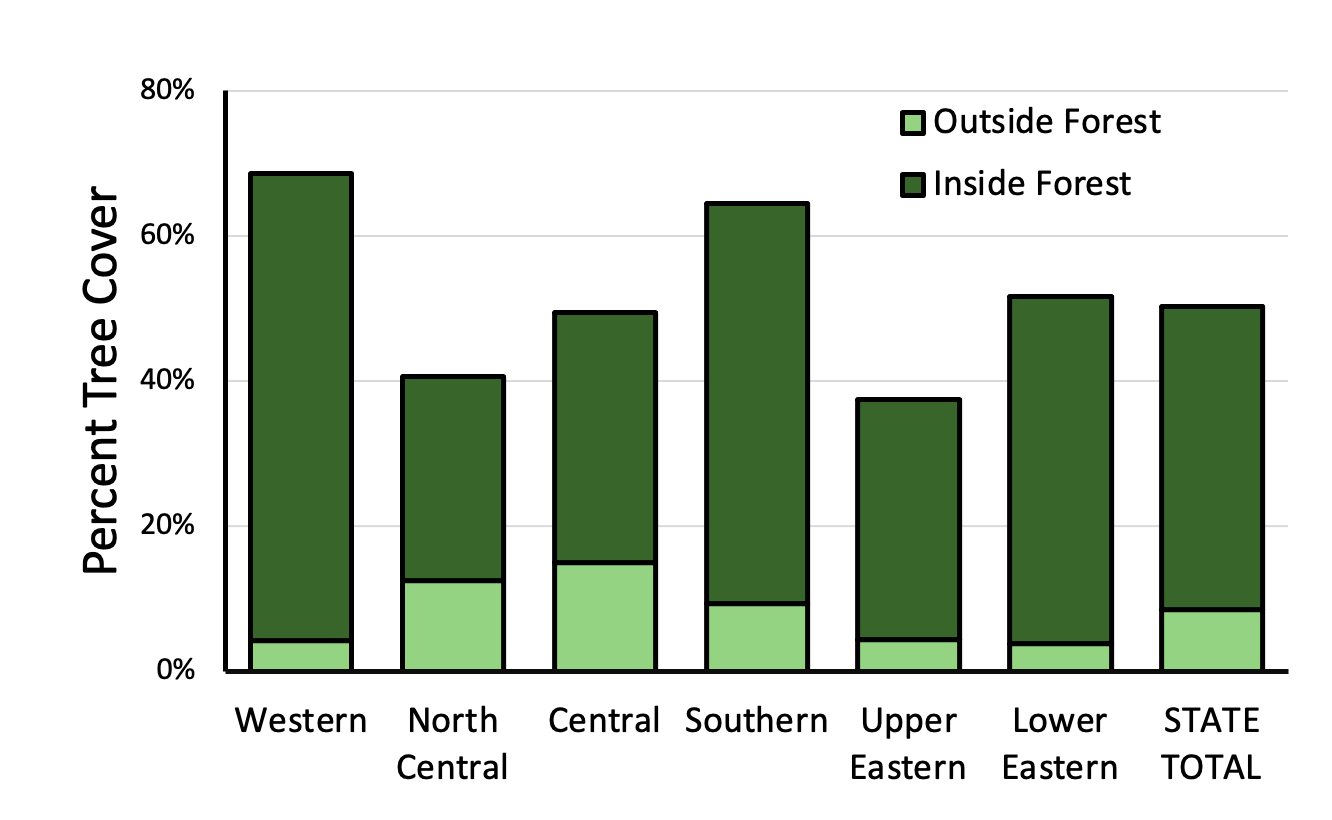

Forest and Tree Canopy Changes

We note that patterns and drivers of tree canopy change (including tree canopy within and outside of forests) vary regionally. All but one region lost forest cover, and the region that gained was the Lower Eastern Shore region where the timber industry is active, signaling regrowth after extraction. All regions but Central Maryland experienced a net gain in tree canopy outside forests, indicative of forest fragmentation and tree planting. Central Maryland, representing the rapidly urbanizing Washington, D.C. suburbs, was the only region that experienced a loss of tree canopy cover from outside and within forest (Figure ES-2, p. 12). The distribution of tree canopy loss is highly skewed — two counties, Montgomery and Prince George’s, accounted for more than 44% of the state’s total tree canopy loss to development and six counties accounted for just under 70% of its tree canopy loss (see Figure 22 and Table 14 in the full report). These counties are Prince George’s, Montgomery, Anne Arundel, Charles, Calvert and Baltimore (Table 14 and Figure 22). Though there was a statewide trend toward forest fragmentation and development (Figure ES-3, p. 12), we also observed transitions of developed land to tree canopy, indicating an effort toward urban greening. The transition of forests to wetlands in coastal counties may be indicative of sea level rise. A parallel analysis found that Priority Funding Areas for development were more vulnerable to tree canopy loss, further indicating development as an important driver of change in the state.

Protected Areas Slow Forest Loss and Are Also a Source of Tree Canopy Gain

In 2018, 33% of Maryland’s forests and 9% of tree canopy outside forests were located within protected areas. Protected lands experienced a significantly lower rate of forest loss and a much higher rate of tree canopy increase compared with statewide rates. Protected areas had a net gain of over 2,200 acres of total tree canopy, demonstrating that protected areas offer a source of tree canopy gain in addition to protecting forests from loss.

Forest Mitigation Banking

Across the state, 81.1% of reported mitigation bank acres protect existing forest, with newly planted forest only making up 18.9% of forest bank acres. This suggests that steps may need to be taken to encourage the creation of planted forest banks, since forest banks can no longer be created from existing forest (at least until June 30, 2024 per the provisions of the Tree Solutions Now Act of 2021). The evidence does not suggest a meaningful relationship between fee-in-lieu rates and the market for mitigation banks. However, higher fee-in-lieu rates could stimulate the creation of newly planted forested mitigation banks in the future. The market for forest mitigation banking varies considerably between counties.

Tree Planting Programs throughout Maryland

In 2018 and 2019, government and private tree planting programs were responsible for the planting of an estimated 1,853 cumulative acres, more than half of which was in response to the Forest Conservation Act (Task 7). This trend toward increasing tree planting should continue and accelerate with implementation of the Tree Solutions Now Act of 2021 that sets the goal of planting an additional 5 million trees (~12,500 acres) over the eight-year period from 2023 to 2031. There is ample land area providing opportunity for planting trees; this study identified over 373,500 acres of potential afforestation and reforestation sites in Maryland on non-agricultural lands. Planting only 3.3% of the identified area would enable Maryland to reach its Tree Solutions Now Act goal.

Selected Summary Statistics

General and Regional Information:

- 3,095,000 acres of forest and tree canopy outside of forest exist within Maryland for 2018 (or 48% of the state’s total land area).

- Allegany County has the most percent tree canopy cover (forest and tree canopy outside of forest), while Baltimore City has the least.

- 373,506 acres of potential afforestation and reforestation exist throughout the state.

- All core forest sizes (large, medium, small) decreased in mean and median area between 2013-2018, except for a slight median increase in large cores.

- Census urbanized areas experienced a net decrease of 13,164 acres of tree canopy, with the largest losses around the Washington, D.C. and Baltimore suburbs.

- Eight jurisdictions have reached the 2014 Chesapeake Bay Agreement goal of 70% forested riparian areas; four jurisdictions have under 50% tree canopy cover in riparian areas.

- Timber harvests on both private and state lands from 2013 to 2021 total 149,156 acres; Garrett County had the highest total harvest, consistent with its large forested acreage.

- Priority funding areas (PFA) experienced a greater loss of forest and tree canopy outside of forest within them (9,583 decrease) compared to non-PFA areas.

- There is a lower rate of forest loss in priority protection areas compared to the state average (0.44% vs 0.70%, respectively), indicating while protected and sensitive lands still experience loss, that regulations to protect the land are working to preserve forest.

Fragmentation, Disturbances, Diseases and Insects:

- Patches of forest increased by 3,252 acres from 2013-2018.

- Forest edges are the predominant fragmentation type (by acreage).

- Suppressive vegetation has the most detrimental impact on forests in terms of disturbances.

- Invasive plant species, multiflora rose most commonly, were found across two-thirds of the USDA Forest Service’s Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) plots across the state.

- The invasive Emerald Ash borer has impacted an estimated 83% of ash volume in the state; forests and trees across the state are otherwise also at risk from Hemlock Woolly Adelgid and Beech Bark Disease.

- Western watersheds of the state are most at risk of insect and disease, with more than 25% of treed areas at risk in some regions, and moderate risk across central Maryland and the Eastern Shore.

Programs:

- 33.2% of forests in the state are in existing protected lands; there was only a slight decrease (0.03%) in forest within existing protected lands from 2013-2018, again indicating protecting land is conducive to preserving forest.

- 18 of the 22 counties governed by the Forest Conservation Act (FCA) have provisions for forest mitigation banking programs, and mitigation banks have been created in 15 of those counties.

- The market for banking varies greatly between counties, with the percentage of development projecting within a county that rely on banking credits for mitigation range from 0 to 80%.

- Across the state as a whole, forest mitigation banks are dominated by previously existing forest, which comprises 13,997 acres or 81.1% of reported forest bank area, with newly planted forest banks only making up 3,261 acres or 18.9% of bank area.

- Maryland has a number of private and government tree planting programs that vary greatly in purpose and scale. In 2018 and 2019, approximately 550,533 trees and an additional 477 acres were planted through these programs.

Review of the Forest Technical Study's Finding

By Dr. Aditi Dubey, Research Associate at the Hughes Center

Background: This post is the first in a series discussing the most comprehensive study of Maryland’s forest cover and tree canopy ever completed. The Maryland Senate enacted a bill authorizing the study in 2019 to improve the statewide inventory of forest and tree canopy cover, assess forest and tree canopy change, and evaluate the effectiveness of Maryland’s forest and tree programs. It was commissioned by the Harry R. Hughes Center for Agro-Ecology and conducted with the Chesapeake Conservancy and the University of Vermont Spatial Analysis Lab.

As the Forest Conservation Act reached 30 years in practice in 2021, this is an important occasion to mark the successes of Maryland’s forest protection policies. And we could also reflect on opportunities to leverage forests and tree canopy further to enhance benefits for habitat, water quality protection, climate resilience and mitigation, human health and environmental justice.

“The findings from this study are key for decision-makers at both the statewide and local levels as they consider future strategies for trees and forests," said Hughes Center Executive Director Dr. Kate Everts. "This study comes at a critical time in Maryland as populations continue to increase and as we consider the future of Chesapeake Bay restoration.”

Over the coming months, we will cover each section of the study, starting here with the survey and mapping of Maryland’s forest cover and tree canopy. We’ll also post these stories online on our website on the Forest Technical Study’s main page here.

Existing Forest Cover and Tree Canopy

The Hughes Center surveyed Maryland’s forest and tree cover using an innovative new high-resolution land use and land cover data set combined with medium-resolution satellite imagery and ground-level data. This data set, spanning 2013 to 2018, has a resolution of one meter, which lets us monitor individual trees inside and outside forests for the first time, allowing analysis of changes at a local scale.

We found that forest covers about 2.5 to 2.6 million acres or 39 to 42% of Maryland’s total land area, with non-forest tree canopy bringing the total tree cover up to about 50%. Tree canopy in the state varies significantly by region, with the highest proportions of tree cover found in Western and Southern Maryland (Figures 1 & 2). The lowest tree cover is in North-Central Maryland, which includes Baltimore City, the most urbanized part of the state, and the Upper Eastern Shore, where wetlands and low-lying vegetation are common.

Looking at changes in tree cover over time, all the data sets used show a slightly decreasing trend, with estimates based on the different data sets ranging from 0.02% to 0.2% of forest loss annually. At the same time, the high-resolution data set also indicates a 6000-acre increase in tree cover outside forest, indicating a potential trend toward increased forest fragmentation but also greening of urban, suburban and agricultural areas.

While overall tree canopy loss in Maryland is relatively low, and is trending towards stabilization, there is more cause for concern when considering regional data. Conversion of forest for development purposes is the leading cause of canopy loss in the state, and Central Maryland counties with rapid development and population growth are experiencing the highest rates of loss as well as high levels of forest fragmentation. Prince George’s and Montgomery counties alone make up more than 50% of canopy loss to development. The findings from this study will help develop strategies to mitigate this forest loss, as discussed further below.

Potential for Afforestation and Reforestation

Maryland must plant new trees and protect existing ones to meet tree canopy, forest cover and water quality goals. The study analyzed potential afforestation and reforestation opportunities in the state, identifying about 374,000 acres of plantable areas.

Much of this land is likely unfeasible for tree planting due to factors such as cost and landowner interest. However, planting even a fraction of the identified area would allow the state to meet its goals. Two of the counties with the highest plantable acreage are Prince George’s and Montgomery. As discussed previously, these counties are also the ones that have lost the most forest to development. Therefore, this data can help identify opportunities for tree planting in regions most vulnerable to continued forest loss.

Read the “Technical Study on Changes in Forest Cover and Tree Canopy in Maryland” here.

Additionally, an online story map provides the opportunity to view and interact with data and results produced to support this study: cicgis.org/portal/apps/storymaps/stories/b519e88ccc8c4c4c8d4c870f64e210ed.