University of Maryland Research Team Seeks the Answer

A saltmarsh sparrow in its crucial nesting habitat of marsh hay cordgrass. Saltmarsh sparrows nest only in tidal marshes of the northeastern US, and their populations are declining rapidly due to habitat loss.

Image Credit: M. Evans

Throughout the world, marsh birds are in decline, with some estimates suggesting their populations are falling by 9% annually, and many species may be extinct by 2050. The primary reason is habitat loss, as the marshes they depend on for survival disappear under the pressures of sea-level rise.

To help reverse this trend, Professor Andy Baldwin and his colleagues from Towson University and the National Audubon Society will study the impacts of a salt marsh restoration project on declining bird populations in the Chesapeake Bay, and the key landscape patterns needed to support the birds that live there.

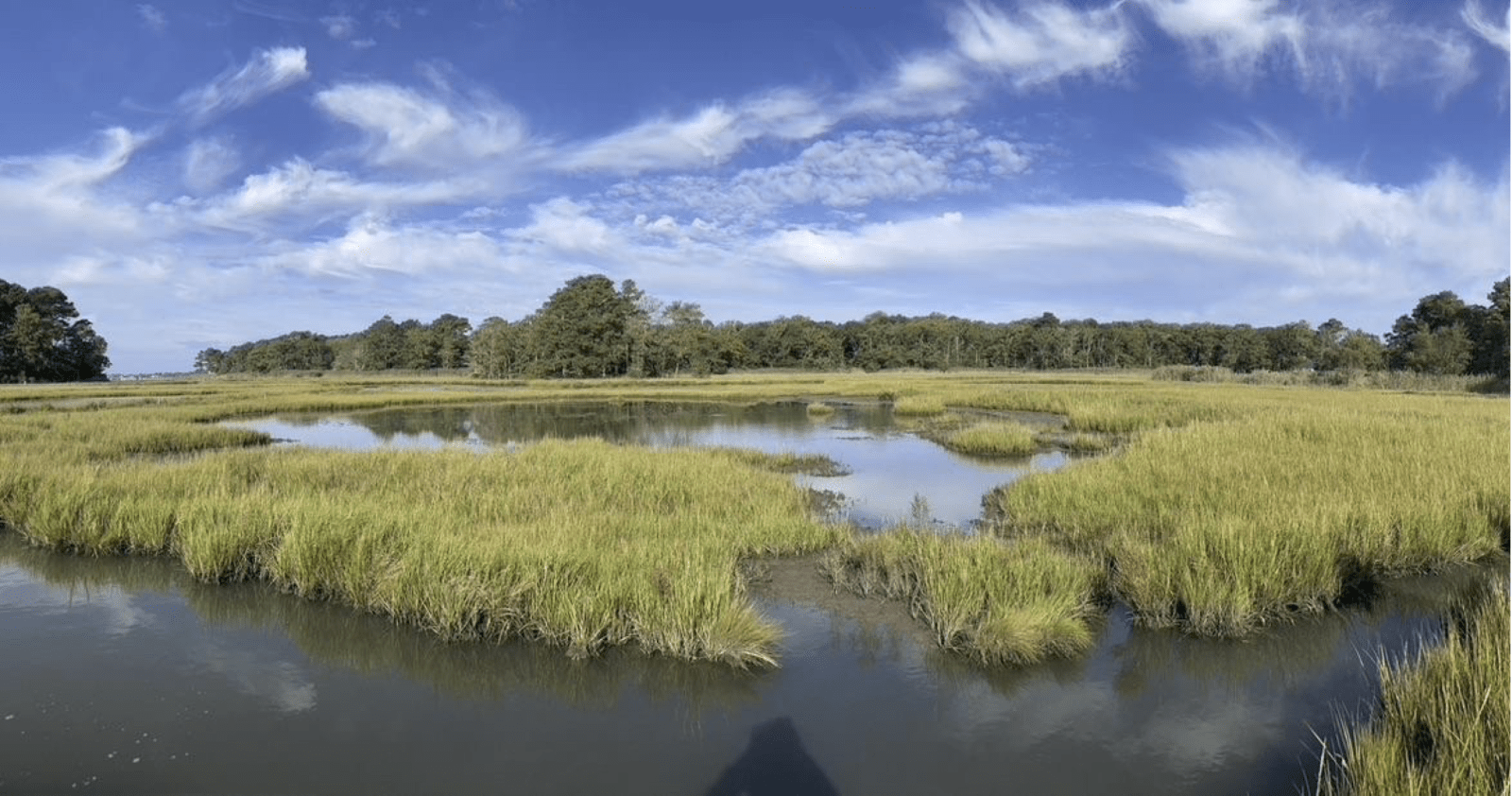

As increasingly higher tides flow into marshes, the water gets trapped into pools that can’t escape back into the open. The pools grow and connect to one another, fragmenting the marshland into a patchwork of small islands that eventually erode away, turning vast swaths of marshland that once supported plants and birds into open water.

Known as open water fragmentation, or “ponding”, this phenomenon is rapidly degrading saltmarshes throughout the Chesapeake Bay watershed, and eliminating critical bird habitat. As a result, restoration projects are planned for thousands of hectares over the coming decade, and Baldwin and his colleagues intend to provide scientific evidence to help guide those projects to ensure they are effective at supporting marsh birds into the future.

The research team will spend the next five years surveying the nesting population of Saltmarsh Sparrows and Seaside Sparrows—two important marsh birds in the region – while the Audubon society works to restore 400 hectares of marshland. The restoration project will use a novel technique called runneling, where channels are dug into the marsh so that pools of water can drain back into the Bay and high tides are no longer trapped behind the marsh.

The team will study the ecosystem in restored areas and non-restored areas, examining how hydrologic restoration using runnels affects salt marsh vegetation, soil, and biogeochemical processes and documenting responses of nesting bird populations. Through this work, they hope to better understand the impacts of fragmentation on marsh birds, measure the outcomes of the restoration techniques and develop a restoration guide to increase restoration efforts throughout the tidal marshes of the Chesapeake Bay.

Throughout the study, AGNR students will assist with the field work and analysis, training and participating in real-world research and conservation practices.

This work is being supported by a $1.5M grant from the National Science Foundation and the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation through the NSF Partnership to Advance Conservation Science and Practice (Award No: NSF-PACSP DEB2529254 )